Cholera impacts 1 million to 4 million people worldwide on an annual basis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). If this bacterial disease is not treated in a timely manner, it can be fatal.

Antarpreet Jutla, Ph.D., an environmental engineering sciences associate professor in the Engineering School of Sustainable Infrastructure & Environment (ESSIE), along with researchers and humanitarian advisors from other institutions, created a one-of-its-kind portal to predict and prevent cholera outbreaks. With a $1 million grant from NASA, the University of Florida (UF) will become one of the first institutions primed to understand the patterns of this disease’s emergence in several parts of the world with the use of prediction tools. The research grant will focus on developing protocols for strengthening anticipatory decision-making for infectious diseases of the future. The team will also harness the power of digital technologies and develop one of the first apps for water-borne infectious disease.

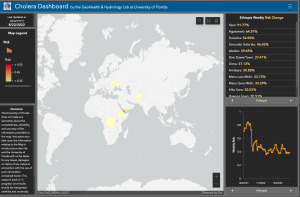

Similar to a forecast model, the Vibrio Prediction Hub houses the Cholera Risk Map, which is an interactive, web information platform that predicts whether there will be a cholera outbreak based on findings derived from weather, climate, pathogen microbiology and water quality. The hub uses an interface similar to the COVID-19 Risk Map that Dr. Jutla created with Rita R. Colwell, Ph.D., an environmental biologist and Distinguished University Professor at the University of Maryland, and Chang-Yu Wu, Ph.D., an environmental engineering sciences professor in ESSIE. The map uses heuristic machine learning and satellite data from weather, climate and sociological processes to predict the risk of future COVID-19 outbreaks.

“We first chose cholera because that was the only pandemic happening in the world for centuries. This disease is unique since we know the solution to limit the outbreak—provide clean water and sanitation facilities—but there are regions in Africa, Asia and some parts of Latin America that don’t have such infrastructure yet,” Dr. Jutla said.

The Cholera Risk Map is updated weekly, and data, such as coastal chlorophyll, temperature, rainfall and population densities, are pulled from NASA satellite sensors. The funding from NASA will allow researchers to expand the data to reach beyond currently selected regions. This funding is part of NASA’s Health & Air Quality program, which was created to address “toxic and pathogenic exposure and health-related hazards and their effects for risk characterization and mitigation.” The goal is to make a real-time assessment and prevent the spread in populations susceptible to outbreaks.

“Earth observing satellites sensors continues to play a critical role in the development, calibration and validation of the algorithms. We continue to get high spatial and temporal resolution of data that can now capture precise location where risk of cholera is likely be high,” Dr. Jutla added. “We will be channeling our resources to the locations where the risk is going to be high, and then telling our end users to collect clinical surveillance data or water samples for microbiological analysis.”

In building a worldwide cholera surveillance and prediction system, Dr. Jutla continues to work with Dr. Colwell, Ali Akanda, Ph.D., an associate professor and graduate director at the University of Rhode Island, the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO).

“The capability of predicting risk of infectious diseases outbreaks weeks in advance provides an incredibly important tool for public health,” Dr. Colwell said. “It offers the opportunity to prepare and thereby save lives and prevent human suffering. It has been a challenge to perfect the model for cholera, and we are delighted to have succeeded.”

Dr. Jutla predicts that it will take four to five years for the hub to be a fully functioning global resource.

Once successful, the research team hopes and plans to develop a holistic infectious water and airborne disease prediction center to preemptively determine the risk of an impending outbreak.

“The transmission of water and airborne infectious diseases is complicated, especially when the causes are associated with a variety of climate, sociological, epidemiological and microbiological processes. Our work suggests that we will be able to harness the power of advances in machine learning to develop predictive intelligence on where and when to expect—and prevent—cholera” Dr. Jutla said.

—

By Reba Liddy

Marketing and Communications Specialist